September 2009

U.S. Military Involvement in Nigeria

U.S. Oil Imports from Nigeria

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA) of the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE), Nigerian oil production averaged 1.94 million barrels per day (bbl/d) in 2008, although the EIA estimates that Nigeria’s effective oil production capacity was 2.7 million bbl/d. Of this, 990,000 bbl/d were exported to the United States. The United States, thus, imported 44 percent of Nigeria’s oil exports, making the country the fifth largest foreign oil supplier to the United States. Nigeria’s oil export blends are light, sweet crudes with low sulfur contents, meaning that they are highly viscous, easy to transport, and comparatively inexpensive to process into gasoline and other petroleum products.

In 1997, the Nigerian government created the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) to manage oil production and exports. The majority of Nigeria’s major oil and natural gas projects (95 percent) are funded through joint ventures with the NNPC as the major shareholder. Shell Petroleum Development Company operates the largest joint venture in Nigeria. Additional foreign oil companies operating in joint ventures with the NNPC include ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Total, Agip, and Addax Petroleum.

The Link Between U.S. Oil Imports and U.S. National Security Policy

Compared to the Middle East, Africa possesses a relatively modest share of the world’s petroleum reserves: approximately 9.4 percent of proven world reserves, compared to 61.7 percent for the Middle East. Nevertheless, the world’s major oil-consuming nations, led by the United States, China, and the Western European countries, have exhibited extraordinary interest in the development of African oil reserves, making huge bids for whatever exploration blocks become available and investing large sums in drilling platforms, pipelines, loading facilities, and other production infrastructure. Indeed, the pursuit of African oil has taken on the character of a gold rush, with major companies from all over the world competing fiercely with one another for access to promising reserves. This contest represents “a turning point for the energy industry and its investors,” in that “an increasing percentage of the world’s oil supplies are expected to come from the waters off West Africa,” the Wall Street Journal reported in December 2005. By 2010, the Journal predicted, “West Africa will be the world’s number one oil source outside of OPEC.”

It is in this context that we must view the world’s growing interest in African oil. African oil output may never reaches the Olympian heights long associated with Middle Eastern production, but it is expected to continue growing in the years ahead at a time when output from many other areas is in decline—and this, more than anything else, makes it significant. According to the DoE, combined oil output by all African producers is projected to rise by 91 percent between 2002 and 2025, from 8.6 to 16.4 million bbl/d. Even if this projection proves overly optimistic, Africa will still figure among the very few major producing areas (the Caspian Sea basin is another) that are expected to post significant production increases in the years ahead. In an environment where any increment in output will be highly prized, Africa is thus a powerful magnet for the world’s giant oil companies.

The United State now obtains between 22 and 24 percent of its total oil imports from Africa, depending on periodic variations in production levels, particularly fluctuations in Nigerian oil production as a result of attacks on oil facilities by MEND and other political unrest in the Niger Delta. As a result, the United States now imports more oil from the African continent than from the entire Middle East, and is expected to get an even larger percentage of its oil imports from Africa in the coming years. In December 2000, the National Intelligence Council of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency concluded that Africa would be supplying 25 percent of America’s total oil imports by 2015. Most oil industry analysts now believe that this estimate was too conservative and that Africa will actually be supplying a considerably greater percentage of U.S. oil imports throughout the next decade.

Despite the inauguration of President Barack Obama in January 2009, U.S. government policy on the procurement of African oil is largely governed by the National Energy Policy Report—the final report of the National Energy Policy Development Group (NEPDG)—which was issued on May 17, 2001. The NEPDG was chaired by Vice President Dick Cheney, a high-level body appointed by President Bush in February 2001, and its final document is often referred to as the “Cheney report.” In the most general terms, the report calls on the federal government to undertake numerous initiatives to substantially increase the nation’s supply of energy, including energy derived from petroleum. As is well known, these initiatives include measures aimed at increasing oil output from domestic U.S. sources, most notably by commencing drilling on the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). But because America’s need for energy is expected to expand substantially in the years ahead, the report also calls for increasing U.S. reliance on foreign sources of energy.

In light of Africa’s unique ability to increase its oil output in the years ahead, the Cheney report highlighted Africa’s potential to supply an ever-increasing share of America’s energy needs. “West Africa is expected to be one of the fastest-growing sources of oil and natural gas for the American market,” the report states. Moreover, “African oil tends to be of high quality and low in sulfur, making it suitable for stringent refined product requirements.” Particular mention is made of the oil potential of Nigeria and Angola. Nigeria’s 2001 production is estimated at 2.1 million bbl/d in the report, and that country is said to harbor “ambitious production goals as high as 5 million barrels of oil per day over the coming decades.” Angola is also described as a “major source of growth,” with the potential “to double its exports over the next ten years.” On this basis, the Cheney report calls for vigorous action by the United States to promote increased oil output in Africa and to channel these additional supplies to markets in the United States. To accomplish this, American oil companies are encouraged to increase their investments in Africa and African countries are encouraged to welcome and facilitate such investment.

The Bush administration also sought to enhance U.S. access to African oil in order to reduce—to some degree, at least—American dependence on the ever-turbulent Middle East. While it is impossible to escape dependence on the Middle East altogether, the Cheney report notes, it is important to reduce U.S. vulnerability to supply disruptions caused by Middle Eastern instability as much as possible – a strategy known as “diversification.” “Concentration of world oil production in any one region of the world is a potential contributor to market instability,” the report notes. Accordingly, “encouraging greater diversity of oil production…has obvious benefits to all market participants.” In accordance with this outlook, the Cheney report calls for vigorous U.S. efforts to increase imports boost from all potential alternatives to the Middle East, but West Africa is viewed with particular favor in this regard because many of its most promising new fields are located offshore, in the Atlantic Ocean, and thus safely removed from the strife and disorder of the African mainland. “Technological advances will enable the United States to accelerate the diversification of oil supplies,” the report notes, “notably through deep water offshore exploration and production in the Atlantic Basin,” particularly West Africa.”

The direct linkage between growing U.S. dependence on oil imports from Africa—and particularly from Nigeria—is based on the assertion that U.S. national security—and our continued enjoyment of the “American way of life”—requires unimpeded access to African oil. Commenting on this development, the former U.S. ambassador to Chad, Donald R. Norland, told the Africa Subcommittee of the U.S. House International Relations Committee in April 2002, “It’s been reliably reported that, for the first time, the two concepts – ‘Africa’ and ‘U.S. national security’ – have been used in the same sentence in Pentagon documents.” Michael A. Westphal, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for African Affairs, also noted this linkage in a Pentagon press briefing on April 2, 2002. “Fifteen percent of the U.S.’s imported oil supply comes from sub-Saharan Africa,” he declared, and “this is also a number which has the potential for increasing significantly in the next decade.” Walter Kansteiner, the Assistant Secretary of State for Africa, further acknowledged the national security implications of African oil during a visit to Nigeria in July 2002. “African oil is of strategic national interest to us,” he declared, and “it will increase and become more important as we go forward.”

As a result, the “Carter Doctrine,” proclaimed by President Jimmy Carter in January 1980 has been extended to Nigeria, the rest of Africa, and—indeed—the entire world. In his final State of the Union Address, President Carter designated the free flow of Persian Gulf oil as a “vital interest” of the United States and declared that this country would use “any means necessary, including military force,” to defend that interest. To implement this policy, widely known as the “Carter Doctrine,” the U.S. Department of Defense established the U.S. Central Command (Centcom) to oversee U.S. military operations in the Gulf area and built up a substantial military basing infrastructure in the region. Later presidents subsequently cited the Carter Doctrine as the basis for U.S. combat operations during the Persian Gulf War of 1991, the war in Afghanistan from 2001 until the present, and the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

U.S. Security Assistance to Nigeria, FY 1999-2010

In the late 1990s, when U.S. policymakers began to recognize the national security implications of America’s growing dependence on African oil (well before this linkage was explicitly and publicly acknowledged), the U.S. government began to dramatically increase U.S. military involvement in Africa to provide support to undemocratic and repressive African regimes in countries that were major sources of American oil imports-like the government of Nigeria—and to regimes that were willing to act as surrogates or proxies for the United States and use their military forces to protect U.S. interests on the continent, like the governments of Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda.

Thus, in 1997, President Bill Clinton established the Africa Crisis Response Initiative (ACRI), the first of a whole array of new military programs aimed that have been created in the past decade to provide increasing amounts of U.S. security assistance to African regimes and to expand U.S. military activities on the continent. In 2004, ACRI was expanded and renamed the African Contingency Operations Training and Assistance (ACOTA) program. American military involvement in Africa escalated rapidly after the inauguration of President Bush in 2001 and has been continued by the Obama administration.

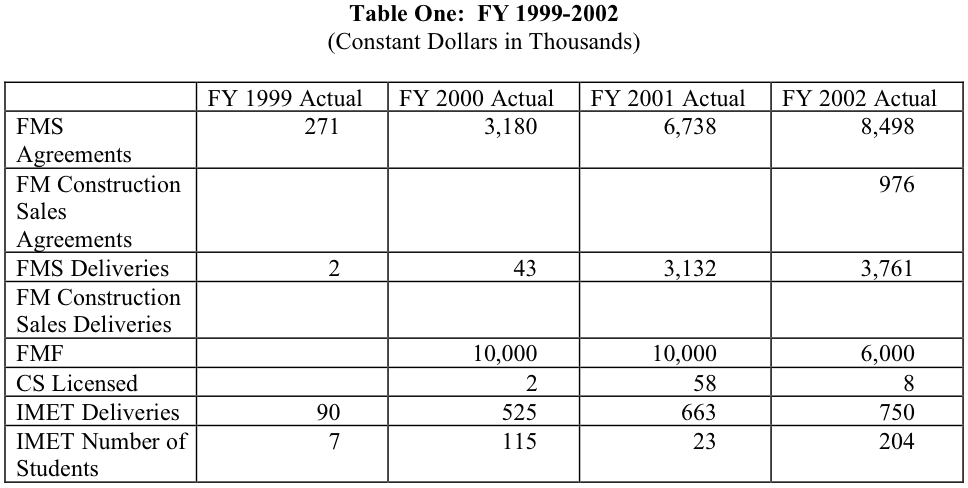

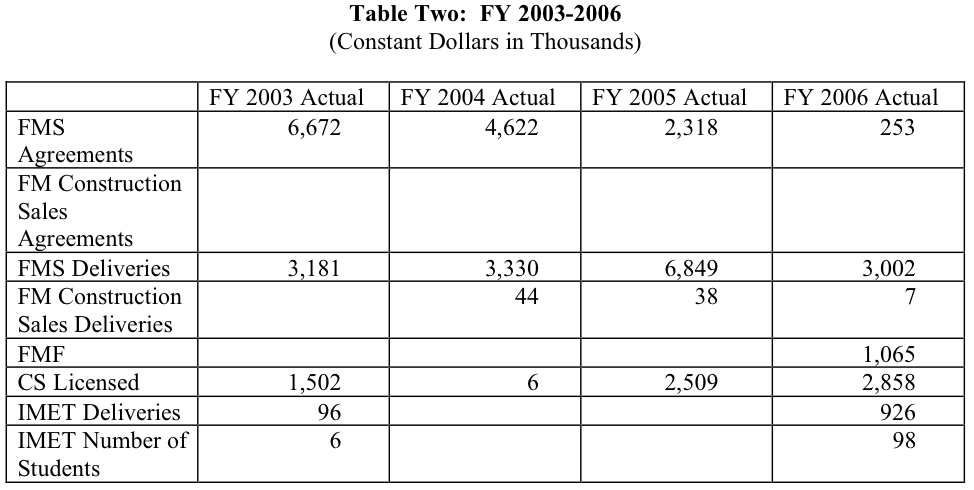

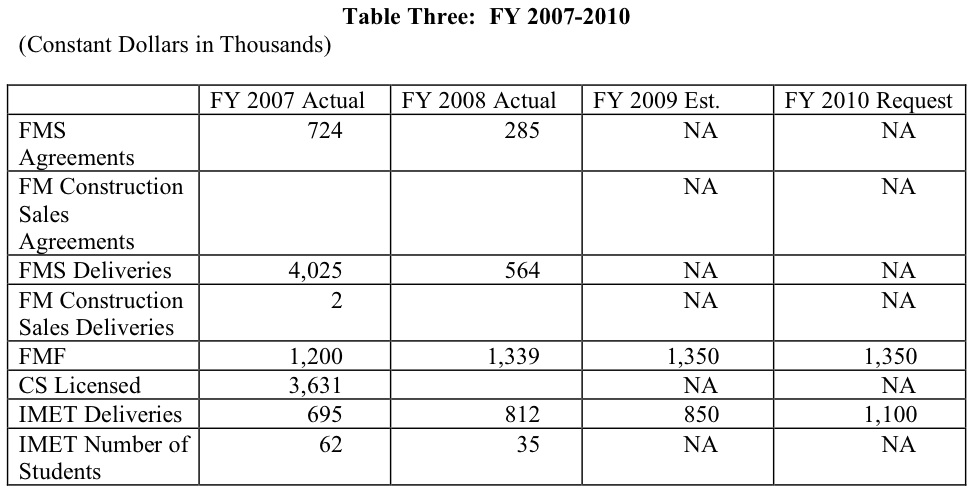

Increasing levels of U.S. security assistance to Nigeria have been a central feature of this escalating military involvement. And it has been explicitly justified as a means to ensure that the United States continues to have access to the oil resources of the Niger Delta. Thus, the FY 2006 Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations notes Nigeria’s “importance as a leading supplier of petroleum to the U.S.” and the fact that “Nigeria is the fifth largest source of U.S. oil imports.” Therefore, according to the Budget Justification, “disruption of supply from Nigeria would represent a major blow to the oil security strategy of the U.S.” It is noteworthy that such honest explanations of U.S. security assistance to Nigeria have been omitted from the annual Budget Justifications since then. The following tables presents data on U.S. security assistance programs for Nigeria over the past decade.

Table One: FY 1999-2002

(Constant Dollars in Thousands)

Table Two: FY 2003-2006

(Constant Dollars in Thousands)

Table Three: FY 2007-2010

(Constant Dollars in Thousands)

Abbreviations:

CS = Commercial Sales

Est. = Estimate

FM = Foreign Military

FMF = Foreign Military Financing

FMS = Foreign Military Sales

IMET = International Military Education and Training

NA = Not Available

Sources: U.S. Defense Security Assistance Agency, Historical Facts Book as of September 30, 2008 and U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations, Fiscal Year 2010.

In addition, the United States delivered four surplus U.S. Coast Guard Balsam-class coastal patrol ships in 2003 through the Excess Defense Articles program of the U.S. Defense Security Assistance Agency. These ships had a total value of more than $4.1 million at the time they were delivered to Nigeria.

Nigeria is also one of the countries that are eligible to receive additional U.S. security assistance through the Trans-Saharan Counter-Terrorism Partnership program. And Nigeria receives further U.S. security assistance through ACOTA, the Anti-Terrorism Assistance program, and the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) program. The level of funding for Nigeria is not available for most of these programs. But we do know that Nigeria is scheduled to receive an estimated $720,000 in assistance through the INCLE program in FY 2009 and that the Obama administration requested $2 million in INCLE funding for Nigeria for FY 2010.

Future U.S. Security Assistance to Nigeria for Military Operations in the Niger Delta

On 12 August 2009, during her trip to Africa, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton met with Nigerian Foreign Minister Ojo Maduekwe. Following the meeting she applauded the efforts of the Nigerian government to establish “security in the Niger Delta,” and stated, “We support the Nigerian Government’s comprehensive political framework approach toward resolving the conflict in the Niger Delta.” She went on to say that “the process, as it was explained to me by several of the ministers who were present, is incorporating the region’s stakeholders as absolutely essential, focusing on the region’s development needs, separating the militants and the unreconcilables from those who deserve amnesty and want to be part of building a better future for that part of Nigeria. And we have offered, again, our support and that of the international community.”

In answer to a reporter’s question, Secretary Clinton said that she had also met with the Nigerian Defense Minister, “and he had some very specific suggestions as to how the United States could assist the Nigerian Government in their efforts, which we think are very promising, to try and bring peace and security to the Niger Delta. We will be following up on those. There is nothing that has been decided. But we have a very good working relationship between our two militaries. So I will be talking with my counterpart, the [U.S.] Secretary of Defense, and we will, through our joint efforts, through our bi-national commission mechanism, determine what Nigeria would want from us for help, because we know that this is an internal matter, we know this is up to the Nigerian people and their government to resolve, and then look to see who we would offer that assistance.”

As this statement indicates, there is little doubt that the Obama administration will provide even more security assistance to the Nigerian government in the future. Moreover, it is clear that this security assistance will be intended specifically the Nigerian government to use for military operations in the Niger Delta.

U.S. Army Preparations for Possible Direct American Military Intervention in Nigeria

In May 2008, the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, hosted “Unified Quest 2008,” the Army’s annual war games to test the American military’s ability to deal with the kind of crises that it might face in the near future. “Unified Quest 2008” was especially noteworthy because it was the first time that the war games included African scenarios as part of the Pentagon’s plan to create a new military command for the continent: the Africa Command or Africom. No representatives of Africom were at the war games, but Africom officers were in close communication throughout the event.

The five-day war games—co-sponsored by the Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), the Special Forces Command, and the Joint Forces Command—were designed to look at what crises might erupt in different parts of the world in five to 25 years and how the United States might handle them. In addition to U.S. military officers and intelligence officers, “Unified Quest 2008” brought together participants from the State Department and other U.S. government agencies, academics, journalists, and foreign military officers (including military representatives from several NATO countries, Australia, and Israel), along with the private military contractors who helped run the war games: the Rand Corporation and Booz-Allen.

One of the four scenarios that were wargamed was a test of how Africom could respond to a crisis in Somalia—set in 2025—caused by escalating insurgency and piracy. Unfortunately, no information on the details of the scenario is available.

Far more information is available on the other scenario—set in 2013—which was a test of how Africom could respond to a crisis in Nigeria in which the Nigerian government is near collapse, and rival factions and rebels are fighting for control of the oil fields of the Niger Delta and vying for power in that oil-rich country, the sixth largest supplier of America’s oil imports.

The list of options for the Nigeria scenario ranged from diplomatic pressure to military action, with or without the aid of European and African nations. One participant, U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Mark Stanovich, drew up a plan that called for the deployment of thousands of U.S. troops within 60 days, which even he thought was undesirable. “American intervention could send the wrong message: that we are backing a government that we don’t intend to,” Stanovich said. Other participants suggested that it would be better if the U.S. government sent a request to South Africa or Ghana to send into Nigeria instead.

As the game progressed, according to former U.S. ambassador David Lyon, it became clear that the government of Nigeria was a large part of the problem. As he put it, “we have a circle of elites [the government of Nigeria] who have seized resources and are trying to perpetuate themselves. Their interests are not exactly those of the people.” (Brackets in original text)

Furthermore, according to U.S. Army Major Robert Thornton, an officer with the Joint Center for International Security Force Assistance at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, “it became apparent that it was actually green (the host nation government) which had the initiative, and that any blue [the U.S. government and its allies] actions within the frame were contingent upon what green was willing to tolerate and accommodate.”

As he explained in a detailed report that he posted on the web, “as the interactive process continued we realized that the host nation had much more tolerance than the design frame had accounted for: example one of the groups Red represented [the rival factions and the rebels] sponsored an assassination attempt from within the host nation’s V.P.’s [Vice President’s] body guard against the President—Blue thought this would be the event that convinced the President to accept our appraisal and recommendations—Green responded by hiring the best western protection service oil money can buy and by waging a brutal COIN [counterinsurgency] campaign against the primary opposition group of a type that would be politically and culturally unavailable to the U.S. but well within the tolerance of green. At that point we realized that the logic which underpinned the design frame was faulty—and a euphemism emerged “if your partner is lame, you must reframe.” While the logic said a government will not willingly create suicide might be sound, that logic did not extend to a government that did not see suicide as its only option. So while the framework identified the government as loosing control and failing, the host nation government did not believe it was. In other words the understanding of the host government’s tolerance was flawed. However, the process is what allowed that to come out.”

As a result, the Blue team began to discuss the possibility of direct American military intervention involving some 20,000 U.S. troops in order to “secure the Oil.” According to Thornton, “we also discussed the need to continue dialogue with Green as well as begin covert discussions with potential rivals (some of Red)—here you had an interesting emergence as some of Red’s goals are more in line with Blue than Green’s were, and a possibility that Red may become Green. Through interaction we found that Green would be willing to receive greater IO [international organization] and NGO aid to the Humanitarian Crisis in the North, which would allow it some freedom of maneuver (both politically and physically) in the Delta region– as such we explored ways to increase capacity of the IOs and NGOs through logistics, and C2 [command and control] while maintaining the lowest possible U.S. signature inside the host nation – e.g. build capacity in the broader distribution system and build interoperability in the C2 structure as well as thicken their networks and provide ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] support to the HR [humanitarian relief] effort.”

Then, Thornton reported, “the next event was the successful Coup by Red – which in turn meant Red became Green. The new Green now had a sincere interest in gaining legitimacy and credibility, and as such was more open to our increasing HR aid. The remainder of the Red Groups now saw an opportunity that did not exist before of new ways to realize their own political objectives and were willing to meet with the new host nation government, as such there was a window of stability. Our assessments now turned to establishing the tolerances of what form that increased assistance could take under the new government. We learned through the framing process that the system would only tolerate a certain amount of energy (you could also consider it as a question of how much capacity it could/would absorb) before the outcomes changed.”

This said Thornton “created a new opportunity for Blue. Blue offered Green increased aid and assistance, and created the conditions for a broader relationship that could be built upon as Blue built up trust, and a legitimatized Green now had to govern. Not a perfect ending – still some warts, but it did better achieve the political objective of energy security and regional stability by not protracting the conflict further through our own actions, as well as identifying and reinforcing new conditions that were more congruent with U.S., regional and partner political objectives.”

The game thus ended without direct U.S. military intervention on the ground, because one of the rival factions executed a successful coup and formed a new government that sought stability. As a result of the coup, “we no longer had tensions. Now what you had was a government interested in reconciliation between various tribal factions, NGOs, and multinational organizations to build capacity for humanitarian relief,” said Thornton.

The Pentagon is well aware that vital tasks of humanitarian relief, as well as post-conflict reconstruction and development are essential to the successful resolution of such conflicts. In fact, said Lieutenant Colonel John Miller of TRADOC, one of the aims of the exercise was to help agencies like the Departments of State and Justice “go to Congress and get the money so they are fully supported,” and thus ensure that the full burden of these tasks doesn’t fall on the military.

At the end of the war game the participants drew up a set of recommendations for the Army’s Chief of Staff, General George Casey, for him to present to President Bush. These recommendations do not appear to be publicly available, so we don’t know what the participants concluded as a result of the war games beyond the lessons mentioned in Thornton’s report. But we do know that since the war games took place in the midst of the presidential election campaign, General Casey decided to brief both John McCain and Barack Obama on the results of the exercise.

We can only wonder what Barack Obama thought of the wargame and what lessons he learned from General Casey’s briefing. One might hope that he came away with a new appreciation for the danger, if not the outright absurdity, of pursuing the strategy of unilateral American military intervention in Africa pioneered by Defense Secretary Robert Gates, who was retained as Defense Secretary by President Obama when he took office, and Army Chief of Staff General George Casey, who also kept his job under the Obama administration. But President Obama has decided instead to expand the operations of Africom throughout the continent. He has proposed a budget for FY 2010 that will provide increased security assistance to repressive and undemocratic governments in resource-rich countries like Nigeria, Niger, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and to countries that are key military allies of the United States like Ethiopia, Kenya, Djibouti, Rwanda, and Uganda. And he has actually chosen to escalate U.S. military intervention in Africa, most conspicuously by providing arms and training to the beleaguered Transitional Federal Government of Somalia as part of his effort to make Africa a central battlefield in the Global War on Terrorism. So it is clearly wishful thinking to believe that his exposure to the real risks of such a strategy revealed by these hypothetical scenarios gave him a better appreciation of the risks that the strategy entails.