ACAS Press Release: Zimbabwe Crisis

Press Release: Zimbabwe Crisis

Press Release: Zimbabwe Crisis

June 24, 2008

4pm EST

The Association of Concerned Africa Scholars (ACAS), has published a special issue on Zimbabwe in the ACAS Bulletin. It introduces the issues surrounding Zimbabwe’s March 29 elections and the current political violence leading up to the June 27th Presidential run-off.

The aim of this special Zimbabwe issue is to provide details and analysis often left out of mainstream news sources. The reader will find a variety of articles from different perspectives, by Zimbabwe experts from the fields of political science, sociology, history, and theology, as well as from seasoned Zimbabwe journalists and an NGO worker reporting from the field. The special issue concludes with a historically-inflected editorial on Zimbabwe’s politics of violence, an open letter to Thabo Mbeki, and provides a listing of on-line resources for further research and information.

The issue was edited by Tim Scarnecchia and Wendy Urban-Mead, and contains articles by (among others): Norma Kriger, Jimmy G Dube, Augustine Hungwe, Sabelo J Ndlovu-Gatsheni, David Moore, Amy Ansell, and Peta Thornycroft.

Contact:

Tim Scarneccia

Kent State University

(330) 672-8904

[email protected]

Wendy Urban-Mead

Bard College

(845) 264-1805

[email protected]

Read the issue here | PDF version: http://concernedafricascholars.org/docs/acasbulletin79.pdf

By Timothy Scarnecchia

In previous elections paramilitary violence came before the actual polling, usually slowing down in the week or so before polling when international election observers and the world press arrived. This has not been the case in the present elections, as violence since the beginning of May has been reported by numerous and diverse sources to be perpetrated by the police, military, and the militias under ZANU-PF control. The intention of this political violence is to terrorize, destroy, and break the will of the MDC and their supporters leading up to the June 27th run-off for the presidential election. What makes the political violence feel like such an excessively brutal betrayal this time around is that it had appeared, for a brief period in April, as if the impressive showing of the MDC in the election and the wide support it had gained would have insulated it from further reprisals from the ZANU-PF before the run-off. After all, wasn’t the world watching this time? This hope for a peaceful campaign was not to happen. As a number of the contributions to this special issue have suggested, violence is the only language ZANU-PF knows, and it has once again unleashed its complete arsenal, resulting in the killing of 50 MDC members as of May 25th, 2008, and the displacement of hundreds of people, including rural villagers, teachers, and activists.

As Kriger and Moore suggest in this volume, the innovation of posting the polling results immediately outside the polling stations should have made it easier for the MDC to prove to officials and the world that they had won-the hoped for “orange” revolution result where a corrupt regime is forced from office after stealing yet another election. Instead, this innovation has only served to become the record keeping apparatus of violence for the military, police, and militias. Soldiers, police, and the party youth were sent to the rural districts and villages where the MDC did well, sent out to “re-educate” the rural population by using tactics developed during the liberation war to punish villagers who were accused of working with the Rhodesian forces. The American Ambassador to Zimbabwe, James McGee, along with his British, Australian, and Tanzanian counterparts, toured the military camps set up for reeducation and visited victims of torture and violence. Ambassador McGee reported being shown ledgers with names of villagers alleged to have supported the MDC in the March 29th elections, lists of names of people to bring in for interrogation and re-education.1 The reports from early May also included collective punishment of those rural villages where records showed the citizens had voted against the ruling party. Public torture has been reported, resorting to the gouging out of eyes and the cutting off of ears. Women have been raped, others have been beaten on their buttocks with plastic pipes and forced to sit on their wounds all day in the sun. A number of villagers died of these injuries or were beaten to death.2

In addition to collective punishment and harassment of rural voters, there have been direct attacks against MDC organizers and candidates. On Monday, May 26th, reports indicated that the body of MDC candidate Shepard Jani was found dumped on a farm near Goromonzi. Jani had lost in the election to ZANU-PF’s Tendai Bright Makunde, but it is believed ZANU-PF is targeting the MDC in Murehwa “…because they are very effective at organizing and had produced very good results for the MDC in the province.”3

Peta Thornycroft provides an account in this issue of the disappearance, murder, and funeral of MDC activist Tonderai Ndira. Thornycroft’s piece shows that the ruling party and its close associates are going after key MDC activists with a greater vengeance and desperation than in the past. Ndira, aged 33, had reportedly been arrested 35 times previously by the state. This time, the way he was taken from his home, tortured, his body mutilated and then dumped at the central hospital morgue shows the extreme forms of violence the ruling party has decided to use.4

While those who carry out these acts do so with a sense of impunity, the leaders hope they have timed the violence to avoid having the world pay attention and actually do something about it. They have worked out this timing fairly well in the past. The world only tunes into Zimbabwe for a brief time and then moves on to the next “crisis”. The xenophobic attacks in South Africa, as clearly as they implicated Thabo Mbeki’s “quiet diplomacy” with Zimbabwe over the past 8 years, also turned the world press’s gaze away from the political violence in Zimbabwe. Concerned scholars need to think of ways to keep the focus on Zimbabwe, and to help disseminate the stories written by so many brave journalists inside Zimbabwe, in South Africa, and elsewhere.

The funeral of Tonderai Ndira may turn out to be a turning point in the history of the opposition. As Peta Thornycroft and others who participated have written, the event symbolized the “war” in Zimbabwe. Just as Zimbabwean nationalism has had a host of martyred heroes, just as the funerals of Steven Biko and so many others in South Africa represented the “no turning back” attitude of the militants in the ANC and PAC, the public display of the MDC burying a hero of the ongoing Zimbabwean struggle against totalitarianism (once again) will likely become a major event in Zimbabwean history. The challenge for those who care about the future of Zimbabwe is not to let this orchestrated campaign of terror and political violence continue without protest.

As David Moore, Augustine Hungwe and Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni have shown in this issue, the reliance on the “sell-out” and “anti-imperialist” rhetoric by the ruling clique continues to gain support from the old guard in the region, but even this tired language has reached its limits.5 How long will it take the region to finally bury the idea that any opposition is a “sell-out” and the only “true” leader is a liberation war hero? The words of the South African leader Pallo Jordan, a member of the ANC National Executive Committee, taken from a speech he gave to parliament in 2003, were recently reprinted in the ANC Today. It is worth reflecting on Jordan’s question to those who blindly defended ZANU-PF because of its liberation war legacy:

“It is an undisputed historical fact that colonialism denied the colonised precisely these protections, subjecting them to the tyranny, not only of imperialist governments, but often to the whims of colonialist settlers and officials. All liberation movements, including both ZANU (PF) and ZAPU, deliberately advocated the institution of democratic governance with the protections they afford the citizen.

All liberation movements held that national self-determination would be realised, in the first instance, by the colonised people choosing their government in democratic elections. Hence Kwame Nkrumah: “Seek ye first the political kingdom!” The content of anti-imperialism was precisely the struggle to attain these democratic rights. In the case of Zimbabwe, democratic rights arrived that night when the Union Jack was lowered and was replaced by the flag of an independent Zimbabwe.”

“The questions we should be asking are: What has gone so radically wrong that the

movement and the leaders who brought democracy to Zimbabwe today appear to be its ferocious violators. What has gone so wrong that they appear to be most fearful of it?”6

The next few weeks before the June 27th run-off election will offer opportunities for the beginning of a new political opening in Zimbabwe. On the other hand, given the history of politics in Zimbabwe it would be naïve and overly romanticized to think the MDC will be able to match the “war” now being launched against it. When the MDC activists do respond to violence with violence, the State will only use this as further rationale for their repression and attacks. As Norma Kriger asked in this volume, is it realistic to think that it is possible to vote Mugabe out of office? What will it take? Will there be any interventions from South Africa, from SADC, from the African Union, the United Nations, or any combination of these? By doing nothing, the regional powers are only prolonging the suffering of the Zimbabwean people and exposing the brave opposition politicians and their activists to a one-sided war, a David and Goliath struggle. By staying on the sidelines, these organizations also feed Mugabe’s rhetoric that it is “the West”, the Americans, the British, and the Australians, who are against him. It is time for some immediate action on the part of those in power in Africa and international organizations. The lack of any concerted and meaningful response from the ANC-controlled South African government, SADC, the AU and the UN has been disgraceful; one can only hope and pray that something will spark them into action before more MDC activists and leaders meet the fate of those 50 already killed since the first election round.

__________

Timothy Scarnecchia, Kent State University, [email protected].

Notes

1. Robert Dixon, “The not-so-diplomatic ambassador to Zimbabwe”, LA Times, May 23, 2008 http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/world/la-fg-diplomats23-2008may23,0,3957643.story

2. Jong Kandemiri and Blessing Zulu, “Politically Motivated Attack on Zimbabwean Villagers Said to Leave 11 Dead” VOA News, 6 May 2008, http://www.voanews.com/english/africa/zimbabwe/2008-05-06-voa55.cfm?rss=war%20and%20conflict

3. Tererai Karimakwenda, “Abducted MDC candidate Jani found dead” (May 26, 2008) SWRaidio.com http://www.swradioafrica.com/news260508/jani260508.htm

4. See Farai Sevenzo very thought provoking account of Ndira’s death for the BBC News “Death of a Zimbabwean Activist” http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7416933.stm

5. See also, T. Scarnecchia, “The ‘Fascist Cycle’ in Zimbabwe, 2000-2005”, Journal of Southern African Studies. 32(2) 2006:221-237.

6. Pallo Jordan, “Democracy is Not a Privilege” ANC Today Volume 8, No. 19. 16-22 May 2008 http://www.anc.org.za/ancdocs/anctoday/2008/at19.htm#art1

By Wendy Urban-Mead

The motivation behind this issue originates in our dismay at the growing urgency of the situation in Zimbabwe. Human rights are being violated with increasing frequency. See, for one example, a report recently published by the Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights (ZADHR). Please read it; a link to the report appears at the end of this issue. We also have personal friends in Zimbabwe who have confirmed that such violations are indeed taking place, and at the hands of people acting in the name of the state. Such a development is in direct violation of all that the liberation struggles against colonialism in southern Africa stood for. We call for all speed and urgency from every agency acting to influence the government of Zimbabwe to allow for the run-off election to be free and fair. Additionally, we insist upon a halt to the intimidation, murder, and beating of persons deemed opposition supporters.

What has Mugabe’s rhetoric wrought, that the call to protect human rights is cast as a

neo-imperialistic impulse? It was from studying the human rights abuses committed against colonized people in Africa, Jews in Nazi Germany, and enslaved Africans in America, that led many of us here in the United States to realize how important human rights are. We became teachers of African history in the interest of, among other things, making Americans aware of the evils of colonial rule as seen in the Smith and Apartheid regimes of the 20th Century. We want to see no more such atrocities committed, such as those suffered by Biko and countless thousands of others, by anyone in power against anyone, anywhere, no matter the race or religion or economic condition of the persons involved at either end of the power scale.

How is it that President Mugabe and his supporters can take the desire for a free Zimbabwe and from that somehow twist it to accuse people like us of neo-imperialism – we who cry out against the beating of grandmothers, children, pregnant and nursing women, beautiful and irreplaceable sons and fathers? The people of Zimbabwe sacrificed their lives and their well-being in the 1970s so that they could be free to express their views, to choose their own leaders, and to chart their own way forward to a prosperity that they could build for themselves. Zimbabwe’s people did NOT make the sacrifices of the liberation war so that Mugabe’s government could send militias out to beat, brutalize, and terrorize them. Haven’t southern Africans had enough of that under the previous regimes that were defeated at such cost and after such long struggle? The world looks to South Africa, the UN, and the SADC, to take courage and convincingly call upon Mugabe and his government to act in protection of its people, immediately, before another precious human life is damaged or lost.

_________

Wendy Urban-Mead, Bard College, [email protected].

Link to the May 9, 2008 Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights (ZADHR) Report, available at kubatana.net: http://www.kubatana.net/html/archive/hr/080509zadhr.asp?sector=HR.

See also the statement in support of the ZADHR by the Physicians for Human Rights:

http://physiciansforhumanrights.org/library/news-2008-04-30.html.

By Anonymous

The following letter was sent out May 8, 2008 from an NGO worker living in Zimbabwe, who offers an eyewitness account from the capital city of Harare as news of political violence began to be heard from individuals, news sources, and rumor. The letter captures well the anger ex-patriates often feel as they hear from their Zimbabwean colleagues of political killings and torture and realize how implicated so many of the “big chefs” are in this violence, how the police and military along with their paramilitary “green bombers” and “war veterans” operate with impunity. Such a realization is jarring and disturbing, scary and depressing. Zimbabweans have no need to be told of this, but those of us outside the country may want to consider the costs such a state and society exact from its people. Zimbabweans have learned to cope with a now-familiar cycle of periods of calm followed by a brutal reaction from a state controlled by forces who know they have everything to lose should they be forced to concede power. TS.

“Letter from Harare – 8 May 2008”

Since the elections on 29 March, I have been trying, without success, to find suitable words with which to convey to those outside the country the experience of being here in this dreadful moment.

Some of my inability to construct a lucid account is surely attributable to the ever-changing rush of events that seems to shift the terrain of what is happening - or what I think may be happening, or what is reported to be happening, or what an army of experts believe to be happening, or what is rumoured to be happening - from hour to hour. The election results will be released tomorrow, or next week or not at all. The Chinese arms ship will dock in Durban, in Beira, in Luanda, or return to China and the weapons will be trucked, or flown to Harare or not. Sixty white-owned farms have just been seized, or 160 farms, or no farm invasion shave occurred. Morgan has won two-thirds of the vote, or a bare majority of the vote or a mere plurality of ballots. Bogus ballot boxes stuffed with phony ZANU-PF votes are seen delivered to the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission to steal the election, the ZEC has been seized by security forces, the police are arresting ZEC personnel. Mugabe and wife have flown to Malaysia or are happily relaxing in their Harare mansion. Mbeki has secretly arranged for Mugabe to step down, or share power or maintain control. There was almost a military coup, or there will be a coup or there has already been a coup and we are under military rule but don’t know it. There will or won’t be a run-off. It will happen in thee weeks, in three months, in a year, not at all. We will be saved by Jacob Zuma, by SADC, by the African Union, by the EU, by no one. On and on and on it goes, baffling, impossible, and we are left dazed, disheartened, flabbergasted.

The Government propaganda machine is in overdrive. “Farmers Attack War Veterans” was Tuesday’s headline. The story told the tale of a white farmer attacking with pepper spray, a band of war vets who happened to “visit” his farm and of three white farmers driving a truck with an improper licence plate. Such lawlessness by whites won’t be tolerated a police official is quoted. The ZBC radio news tells us that MDC thugs are attacking innocent villagers, that MDC leaders are trying forgo the proper legal process and to delay the run-off, that MDC agents have been aiding the return of deposed white farmers to retake the land and restore the old colonial master. I must confess that I find a certain morbid fascination in these ludicrous accounts, brazenly inverting reality, openly reversing victim and perpetrator, mobilizing the rhetoric of sovereignty, rule-of-law, racial-solidarity and patriotism to justify brutal oppression.

Make no mistake: at its core, the story of post-election Zimbabwe is all about violence. Overwhelming, intimidating, sadistic violence unleashed upon the rural black population; anyone – children and the elderly, women and men – perceived to have voted for the MDC, or to be a relative, friend or acquaintance of someone who may have voted for the MDC or to reside in an area that supported MDC. From our Harare island of relative calm and safety, we sit by, helplessly, as their stories trickle and then flood in from the countryside.

Here are some of the accounts that I have heard directly from local sources in the past few days:

• On Sunday evening, one of our local staff described his just-completed visit to his family in the rural Eastern Highlands. When he arrived the village Headman was in hiding, threatened by a roving gang of ZANU-PF youth led by the so-called war veterans. Many young people, he said, had been dragged from their homes, beaten and forced to chant ZANU-PF slogans. They were then told that they were now recruited into the ruling party and were forced to become part of the youth patrol terrorizing the district each night. If they refused they were beaten. The bus on which he traveled back to Harare on Sunday was stopped several times at impromptu ZANU-PF roadblocks. Youth and War Vets clambered on board beating those suspected of supporting the opposition and demanding that everyone chant ZANU-PF slogans and sing “patriotic songs.” Those who resisted were dragged out and beaten, as the police calmly watched from the sidelines.

• On Tuesday a colleague at work came into my office to show me a text message she had just received on her cell-phone. It announced that Monday night the younger brother of her recently diseased fiancé, suspected of being an MDC supporter, had been beaten to death by a group of naked ZANU-PF militants. Naked! Apparently, many others in the village had been beaten and terrorized.

• A friends’ daughter who broke her arm in a playground accident on Monday afternoon was scheduled to have a pin inserted and the bone set on early Tuesday. The parents told us that the operation had to be repeatedly delayed, as the medical staff rushed to attend to numerous seriously-injured victims of ZANU-PF violence who continuously streamed into the private clinic.

• Yesterday an NGO colleague reported seeing thousands of people on the Mazoe road – just north of Harare – carrying what possessions they could and apparently fleeing towards the city. Today VOA reported that eleven people had been murdered and at least twenty more seriously injured in Mazoe North, all victims of ruling-party assault.

• Here is a widely-published account from about two weeks ago, confirmed by several sources. While not directly reported to me, I have found particularly disheartening, as I have a professional link to the key perpetrator, David Parirenyatwa, M.D., the national Minister of Health and Child Welfare and a ZANU-PF Member of Parliament. Together with two other ruling-party politicians, the good doctor, brandishing an AK-47, is said to have invaded a peaceful MDC meeting, threatening and intimidating those in attendance and demanding that they attend a ZANU-PF rally instead. “There is no place in this district where MDC supports will be safe”, he reportedly told the crowd. This from the senior most Government official charged with safeguarding the public health and the well-being of Zimbabwe’s children.

Since my arrival in Zimbabwe fourteen months ago, numerous people here have referred to the apocryphal tale of the frog blissfully swimming in a pot of water as the temperature gradually increases to the boiling point, as perhaps a fit analogy descriptive of our own adaptability to an ever-worsening scene, an ever more menacing and manifest evil. We are well and still quite safe, but we can definitely detect the heat of the water.

By Peta Thornycroft

Tonderai Ndira’s body was identified in the mortuary at Harare’s Parirenyatwa Hospital by a bangle around what had been his wrist.

He had been dead a long time, or at least a week as it was on May 14, in the early hours of the morning that this extraordinary activist, probably the most persecuted political personality in Zimbabwe, was snatched from his working class home in Mabvuku township, eastern Harare.

They came at night, about 10 of them, and in front of his children, Raphael 9 and Linette 6, and his wife Plaxedes, beat him up and then dragged him screaming into a white double cab.

Tonderai Ndira, 33, was certainly Zimbabwe’s most renowned street activist who had been arrested and beaten up and hospitalised scores of times since he began campaigning for democracy in late 1999.

His decomposing, naked body was found in the bush near the old commercial farming district Goromonzi, about 40 km south east of Harare, close to the torture centre run by the security forces, usually the Zimbabwe National Army, where so many Zimbabweans have been worked over since independence.

Hours after his brothers identified the body - it was so decomposed and mutilated that his own father was not sure whether the long, slender remains on the slab was his oldest son - the police began harrassing the family saying they could not have the body for burial.

His brother Cosmos Ndira said yesterday: “He was in the mortuary where they keep the unknown people, the street kids. He was naked. The bangle was given to him by his wife.

“I think Tonde was arrested 35 times, but maybe more, we lost count. We were all so happy after the elections, thinking that the eight years was now over and we could begin new lives.

“We often talked about dying, and Tonde often used to tell us that he would be killed by Zanu PF because he was arrested and beaten up so often.”

Ndira was head of the Movement for Democratic Change’s provincial security department in Harare.

He was detained for five months last year in the pitiful prison cells, unfit for human occupation, and was suing home affairs minister Kembo Mohadi and police commissioner Augustine Chihuri for wrongful arrest.

Despite all the arrests since the MDC was launched Ndira was never brought to trial. All charges, including a two year period when he was remanded every two months, were dropped for lack of evidence.

The police have failed to convict a single MDC activist among the tens of thousands detained in the last eight years.

Ndira was one of the activists who was, occasionally openly critical of the MDC when he believed it had gone wrong.

He didn’t believe in “my party right or wrong” but was a founding member of the party and destined for high office one day although he always saw himself as a background activist.

“I do this for my children. I want them to have a better life than me,” he told journalists who asked him why he kept on going.

His death came on a day when two more MDC activists were buried at the Warren Park cemetery west of Harare. One of their friends was buried last Sunday.

Those three were beaten to death in a rural area about 65 km north east of Harare where most, but certainly not all of the violence has taken place since the March 29 elections.

No one is sure how many people have died since Zanu PF and President Robert Mugabe were defeated in parliamentary and presidential elections. So far 42 victims have been identified by relatives, but many people believe the real toll is much higher especially in remote parts of northern Zimbabwe. If there are any Zanu PF victims, police and the party have failed to provide details.

At least 600 terrified people including dozens of nursing mothers and babies are sheltering at the MDC’S Harare headquarters, Harvest House.

They have no blankets nor food, and the ablution facilities are blocked, and the conditions are inhuman as the building is an office block.

So far neither the International Committee of the Red Cross nor the United Nations has even been to inspect or assist the internally displaced, “It is an appalling crisis,” said MDC lawyer Alec Muchadahama yesterday.

“The people are supposed to go to a neutral area so they can get international assistance. Where is a neutral area? Where should they go?” he said.

“This is Zimbabwe’s darkest hour. Will anything or anyone rescue us? Can there be an end to this? We can’t keep up with it,” he said, and admitted he was exhausted.

Scores are in detention including two recently elected MDC MP’s, Iain Kay, Amos Chibaya and Dr Alois Mudzingwa, MDC executive member and close friend of MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai.

Kay was one of the first white farmers to be assaulted by Mugabe’s “war veterans” in 2000, and he was later forced off his farm. He won his seat on March 29 with support from people from his old farming area, around Marondera, 70 km south east of Harare.

He and Chibaya are being charged with incitement to public violence, according to Muchadahama and were due to appear in their local magistrate’s court yesterday.

No one has been arrested in connection with any of the MDC murders, nor in connection with tens of thousands who have been assaulted. No one has been arrested for arson of village after village in the last three weeks either.

“We can’t really keep up with all the deaths and arrests. I have to go and attend to someone else from the national executive who has been arrested.” Mchadahama said.

__________

Peta Thornycroft, Harare, May 22, 2008

By Amy E. Ansell

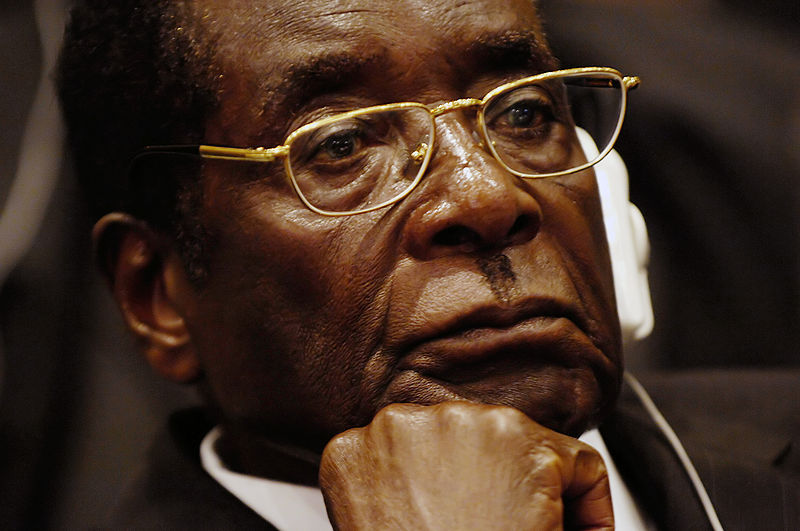

Two months after the March 29, 2008 election in Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe’s defiant fistful image still leers from election posters hanging along the roadsides, boldly displaying the campaign slogan “Defending Our Land and Sovereignty”. State-run media reinforces these twin themes daily as Mr. Mugabe prepares for the June 27 presidential run-off with the tested tactics of stoking racial hostilities and intimidating his foes. International concern mounts over documented evidence of an on-going campaign of violent retribution by the Mugabe regime for its election setback, a campaign that has included renewed farm invasions targeting the few remaining white commercial farmers. Whilst international attention has rightly focused on ZANU-PF’s brutal post-election assault against Zimbabwe’s rural black population, this essay highlights the fate of white commercial farmers as one aspect of the larger state-sponsored campaign of violence and terror in the country that has a particular symbolic resonance.

Background

At the time of Independence in 1980, Robert Mugabe was credited with being magnanimous toward the white farming community, calling for coexistence and reconciliation between blacks and whites: “If yesterday I fought you as an enemy, today you have become a friend with the same national interest, loyalty, rights and duties as myself. If yesterday you hated me, today you cannot avoid the love that binds you to me and me to you.”1 Yet from the beginning there were those who believed liberation would not be complete until all the whites were off the land. These hawks were constrained for decades by a variety of factors, chief amongst them a Constitutional provision that required a ten year period where land would be acquired only through a “willing-seller, willing-buyer” system. When this period came to an end, the Land Acquisition Act was amended in 1992, making it easier for Government to compulsory acquire land, albeit with due compensation. Throughout the decade, land reform was pursued in fits and starts, with changing targets and a series of botched donor initiatives. 2

The situation altered radically in 2000 in the immediate aftermath of Government’s defeat on a referendum for a new constitution. The defeat owed in large part to the emergent political muscle of the newly formed opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which much of the white farming community supported openly. Days after the defeat, invasions of white-owned farms began in an operation labeled “Get Up and Leave”. A central if unofficial component of the Government’s Fast Track Land Reform Program (2000-2002), this Operation led to the displacement of the overwhelming majority of the white commercial farmer population, estimated to be 4,500 in 2000. Two recent surveys of displaced white farmers reveal widespread human rights violations against them perpetrated by farm invaders, financial losses estimated in the amount of US$8.4 billion, and a range of devastating human impacts.3 These human impacts – on health, livelihood, family/gender, and identity – are the subject of a separate research paper. 4

An uneasy truce set in after the worst of the violence receded, although contests between white farmers and Government continued through the Courts. As the extreme bias of the Zanu-PF packed Courts became clear, and as domestic legal remedies became exhausted by 2007, 5 one white farmer – William Michael Campbell, of Chegutu – took Zimbabwe’s land reform program to an international court: the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Tribunal. Campbell leveled three charges: that the land reform program was racist (against whites), that it was unconstitutional since Amendment 17 passed in 2005 prevented white farmers’ right to judicial appeal, and that due compensation has not been paid as required by law. In a hearing before the Tribunal in late March 2008, 73 other white farmers were successfully joined to the case, and all became covered by an interim relief order. The order required that the Zimbabwean Government halt the evictions and take no steps to interfere with peaceful residence and the beneficial use of the farms pending the outcome of a mass hearing set for May 28. During this period of uneasy truce, fissures surfaced in the ruling party over whether or not to allow the remaining white farmers keep their land, and the media reported coalitions of traditional leaders, new settlers and other members of local black rural communities petitioning Government to allow their white farmer neighbors to remain.

The Post-Election Period

This terrain imploded in the aftermath of the March 29, 2008 harmonized election. After a dizzying period when the public and media had little idea what was going on behind the scenes, it soon became evident that Zanu-PF hardliners had gained the upper hand. The upshot for the land question was that what had been a minority view to cleanse the country of all remaining white farmers became more salient. It was in this context that reference to a “final solution” began to be aired. In an address before a trade fair on April 25, Mugabe said: “Let the colonists know this is the final solution”. “The land reform programme under which thousands of Zimbabweans were allocated land taken from the white minority is the final solution to the land question and will never be reversed . . . We are simply claiming our birthright, defending our hard won sovereignty . . . Better all those who shake and quiver at every word of our colonial masters please know Zimbabwe will never be for sale . . . and will never be a colony again.”6

The fresh round of farm invasions intensified, justified in the state media by the spectre of former white farmers reported to be returning en masse from self-imposed exile to re-possess their farm properties in anticipation of an MDC victory that would restore the colonial order. Some reports went so far as to claim that white settlers were intimidating and inflicting violence against “visiting” and “innocent” war veterans.7 An intercepted radio message from PROPOL (police) aired on April 16 stated:

“It has come to the attention of this headquarters that there has been an influx of former white farmers in the country. These former white farmers are visiting farms and challenging current farm owners to return their property which they allege was unlawfully taken away from them. The former white farmers are also conducting meetings clandestinely with the intention of disrupting farming activities . . . Once seen, they should be arrested and detained forthwith for disrupting farming activities.”8

This communication is quite possibly connected to the subsequent arrest of Wayne Munro and three other white farmers in early May. Munro was arrested for shooting at and pepper spraying the crowd during the violent attack against him. Three other white farmers were arrested “after they were seen driving around” in a vehicle with allegedly “fake” registration plates and for weapons’ possession (i.e. violating the Firearms Act). The Herald reported that the “police would not allow any attempts to subvert the law in any part of the country” and quoted Didymus Mutasa, the Minister of State for National Security, Lands, Land Reform and Resettlement, as warning that “by harassing new farmers, the white former commercial farmers were ‘playing with the tail of a lion.”9

Despite such blatant attempts to reverse victim and perpetrator, the reality is that Operation “Final Solution” has involved a violent war of attrition against much of the remaining white farming sector. As in the past, the focus of the campaign has been to make life intolerable for white farmers in order to get them to pack up and leave. Tactics have involved: the sadistic maiming of pets, farm animals and wildlife; death threats; theft or destruction of crops and equipment; and jambanja where the farm family is barricaded on the farm by a noisy and threatening group surrounding the perimeter for days, weeks, and in the case of Digby Nesbitt and his family, for four months. Although the overwhelming majority of victims of violent assault in the post-election period have been black farmer workers, new settlers, and communal dwellers,10 at least two white farmers have landed up in hospital as a result of assault at the hands of invaders. Both the intention and effect of this campaign has been to humiliate farmers and cause trauma, fear, and psychological stress.

Below are synopses of the stories of three white farmers who have endured disruptions in the post election period. 11

• John Borland, a white commercial farmer in Masvingo, has from early April been subject to severe intimidation and verbal abuse by a group of war veterans and youth militia. The invaders announced that they had come to take “their” land, cattle and equipment. Borland and his family were ordered to leave with one suitcase and “go back to the UK” (this despite the fact that Borland is a Zimbabwean citizen, as are 75% of displaced white farmers).12 They accused him of returning evicted white farmers to their farm. His horses have gone missing, the whole of the farm has been pegged, fencing stolen, gates left opened, and cattle from communal land brought in. Pungwes (political reorientation by the Youth Brigade and war veterans) are held nearly every night at a camp set up about 150 meters from the homestead, sometimes “attended” by as many as three hundred farm workers and communal dwellers. The farm staff was ordered not to do any more work for Borland, and eventually became so intimidated that, given the lack of police protection, they all resigned. Borland was then forced to provide his former staff with retrenchment packages, even though they had not been fired but had resigned under duress. The nightly pungwes continue and Borland is constantly hassled by the youth base commander for donations of meat, milk, firewood, even donations to Zanu-PF for t-shirts for the upcoming run-off election.

• Louis Fick, a white farmer in Chinhoyi, had all the locks to his farm removed and new ones replaced by the would-be beneficiary, Edward Mashiringwani, the Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank. His case has been widely publicized in the independent media, no doubt in large part due to justifiable concern over the cruelty on the part of the beneficiary in preventing the feeding of penned livestock (8,000 pigs, 14,000 crocodiles, and 2,000 cattle). For over a month, Fick has had access to his farm and livestock constantly blocked. Since the required daily feeding of livestock has been impossible, the Zimbabwe Society for the Protection against Cruelty to Animals (ZNSPCA) has attempted to intervene, to no avail.13 To date, 82 pigs and 28 crocodiles (as well as 42 crocodile hatchlings) have been found dead. Reports have been issued about terrible squeals being heard as mother pigs denied food for up to six days ate their piglets. When Mashiringwani gave Fick a three-day ultimatum to put in writing what he is prepared to give him, it became apparent that the starving of livestock was being used to gain leverage in negotiations to broker a deal to take over the farm.

• Paul Stidolph, a white farmer in Karoi, has been under siege since April 16th, when his farmhouse was invaded by armed and uniformed soldiers, acting on behalf of the would-be beneficiary, Major General Nick Dube. Although soldiers had been resident on the farm since October 2007, the Stidolph family was allowed to continue living in the farmhouse and operate a registered dairy. This accommodation ended after the election when, on April 8, Dube visited the farm and gave soldiers the order to evict. The Stidolphs were barricaded in their house by an angry crowd of about 100 people, and their son was beaten up. They were given 24 hours to vacate. Since the property is covered under the SADC interim relief order, Stidolph refused. At this point the situation deteriorated and the soldiers threatened to shoot their dogs. Stidolph and his wife retreated to the house with their dogs and locked themselves inside. The soldiers then brought hosepipes from the garden and starting pumping water under the doors in an effort to flood them out. The soldiers only retreated when Mrs. Stidolph put a pistol to her head and threatened to shoot herself dead before she would leave her home alive or see her dogs killed. The soldiers returned later to apologize, insisting they were ordered to do what they did and feared losing their jobs if they failed to carry out their orders. A few weeks later, on May 8, the Stidolph home was invaded again. They were forced to pack their belongings at gunpoint while much of their property was thrown out of the house and destroyed. One soldier told Stidolph that they were being evicted because General Dube and Minister Mutasa were angry they had taken their case to the SADC court.

The major new development this month has been farm disturbances and violence in the Chegutu district, with twenty farms reportedly seized in the province of Mashonaland West.14 Chegutu was quiet the previous month, certainly in part due to the fact that it is the area most closely associated with the SADC Tribunal case. Michael William Campbell’s farm is located there and a group known as the “Chegutu 13” was active in moving the case forward in 2007 before being joined by others in late March. In early May, groups of youth militia moved into the area. On instructions from the local Zanu-PF MP, they moved from door to door of all the farms to evict the farmers, despite the fact that they all enjoy interim relief from SADC. Local police have refused to take action, saying the matter is either “political” or “civil”, suggesting that reports of orders from “high up” that no farmers should receive police assistance in the present wave of farm evictions and violence are in all likelihood are true. When one farmer presented a copy of his interdict in order to stave off eviction, invaders retorted that they were not interested in “any paperwork”.15 It remains to be seen how the SADC Tribunal will respond to such open defiance of its orders by the Zimbabwean Government.

Conclusion

Renewed attacks on white commercial farmers are part and parcel of the more generalized campaign of intimidation and violence spearheaded by Mugabe’s regime in the aftermath of its electoral defeat in the first round. The US Ambassador to Zimbabwe, James McGee, has called the situation a “humanitarian disaster” and released data that there are more than 30,000 displaced persons, 1,300 victims of violence, and 30 confirmed dead.16

In this context, there is some potential, although unlikely, that a turn toward racial violence will occur. A repeated theme in white Zimbabwean discourse is that race relations were on a good footing before the land invasions occurred. True or not, the actions of Government are intent on sowing conflict between white farmers and black settlers/workers. Propaganda is targeted to this purpose, one extreme case being a farm near Bulawayo where new farmers have been warned by Government that the white farmer is involved in an opposition plot to poison their livestock in order to push them off their newly acquired land. Various other mechanisms are employed, too, such as provoking farm workers to demand steep retrenchment packages or prohibiting them from working for white farmers under threat that their huts will be burnt down. There is always the potential that such stoking of racial conflict from above for political gain can take on a life of its own. If it does, it will be but one more aspect of the tragedy that is Zimbabwe under Mugabe’s rule.

_________

Amy E. Ansell, Bard College, [email protected]

Notes

1. International Crisis Group, Blood and Soil: Land, Politics and Conflict Prevention in Zimbabwe and South Africa, Africa Report No. 85, September 17, 2004, p. 31.

2 Ibid.

3 Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum and the Justice for Agriculture Trust [JAG] in Zimbabwe, “Adding Insult to Injury: A Preliminary Report on Human Rights Violations on Commercial Farms, 2000 to 2005”, June 2007; and Justice for Agriculture Trust [JAG] and the General Agricultural and Plantation Workers Union of Zimbabwe [GAPWUZ], “True Sons of the Spoil: Political Purge and Plunder on Zimbabwe’s Commercial Farms”, February 2008.

4 Amy E. Ansell, “Human Impacts: Case Studies of Displaced White Farmers in Contemporary Zimbabwe” (forthcoming).

5 These two claims are the subject of another paper of mine, “The State of Justice on Race and Land in Zimbabwe”, (forthcoming).

6 “No going back on land: President”, The Herald, April 26, p. 1.

7 “War veterans attacked, three farmers arrested”, The Herald, May 5, 2008, p. 1.

8 CFU, “Report on Post Election Farm Invasions and Disruptions”, May 2008, p. 10-11.

9 “War veterans attacked, three farmers arrested”, The Herald, May 5, 2008, p. 1.

10 The terrible violence being inflicted on black rural communities is both more severe and generalized than in the past. For a good treatment, see: The Zimbabwe Association of Doctors for Human Rights, “Statement Concerning Escalating Cases of Organized Violence and Torture and of Intimidation of Medical Personnel”, May 8, 2008.

11 This information is taken from the April and May 2008 reports on post election farm invasions and disruptions compiled by the CFU.

12 Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum, “Adding Insult to Injury: A Preliminary Report on Human Rights Violations on Commercial Farms, 2000 to 2005), June 2007, p. 1.

13 The former director of the ZNSPCA, Meryl Harrison, is credited with saving scores of animals from the invaded farms in the past and has a forthcoming book coming out on the subject.

14 Bernard Mpofu, “20 farms seized in Mash West”, Zimbabwe Independent, May 9, p. 1.

15 CFU, Report on Post Election Farm Invasions and Disruptions”, May 2008, p. 14.

16 These figures were announced at a USAID Partners Meeting in Harare on May 19, 2008.

By David Moore

The following journalistic efforts are those of a political scientist-political economist who has been following Zimbabwean politics and its history since emerging into political puberty in 1971.1 Mixing scholarship and journalism is not always successful: journalistic deadlines are often missed, our articles get cut with no mercy, teaching and administrative wars at the university intervene, and power and phones are off and on in Zimbabwe so contacts are difficult to reach. Articles are sent out hit and miss to editors unknown (not that careful efforts to cultivate allies always work: if a deadline is missed by even an hour, it’s too late; if a word-count is exceeded the editors would rather spike it than cut it down to size, meaning a look at my correspondence with the Mail and Guardian is a woeful experience!) colleagues across the region help and hinder – and one wonders what political toes are being stepped on too hard. Perhaps worse, the titles are never our own.

More importantly, it’s very difficult to stop pontificating from the public intellectual’s secular pulpit, and to cease from hoping against hope that something positively progressive might emerge from the rendering of Zimbabwe’s vicious rent-seeking élites (or ‘bureaucratic bourgeois’, to put a leftist slant on essentially the same process) nightmare. In the end, in response to many colleague’s criticism that I am much too optimistic about the Movement for Democratic Change’s capacity to pull the social democratic rabbit from the evil magician’s hat, I decided to call myself an ‘optimum pessimist’ in an attempt to marry Gramsci’s epigrammatic utterance about the modalities of combining intellect (pessimistic – or simply rigorously realistic) and will (optimistic – people can and do create positive change together). Ultimately, Marx’s ambiguities about people making history only amidst the conditions of historical context they didn’t choose are the only truths. Zimbabwe’s primitive accumulation with its racial twist creates hell for those in the left-leaning pews in the MDC’s and civil society’s broad churches.2 What will emerge from its purgatory is uncertain – and may well be decided outside it borders – but not inevitable. One can only chronicle the positive sides of agency alongside their more successful negative parallels.

To be true to the intent of this project rather than alter the articles in line with retrospective theoretical or narrative rectitude they are reproduced in their entirety. The odd mistake of the moment and an inclination to insert bracketed comments on what I now think I really meant to say to clear up analytical presumptions or what historical changes flowed from that moment, or to insert what the zealous editors spiked, will be kept to a minimum of footnotes. I think the articles tend to capture the moments and their historical context. A few words explaining the context of the articles will preface each selection.

The first piece, ‘Todays’ “imperialists were those who nurtured Mugabe’, tries to present some historical context to the hysterical debates raging now (inspired to a great degree by South Africa’s president’s attempts to invoke pan-Africanism to justify his malign neglect and ‘quiet diplomacy’ vis a vis his neighbour) about whether or not politics in Zimbabwe is driven by an ‘imperialist’ agenda. The hidden agenda in this piece, which was instigated as a response to ZANU-PF’s 2004 effort to deny all NGOs in Zimbabwe any foreign funding, is to say to the strident anti-imperialists: ‘so what if the MDC is partially funded by the Brits and the Yanks: so was Mugabe!’ The point is, the party must have a strategy for the use of these resources so, as Mugabe put it in the early sixties ‘you don’t end up inside the tiger’ of foreign funding (Tim Scarnecchia picked up that wonderful line, from the State Department’s record of its Salisbury representative’s interview with Robert Mugabe, in which he said, in response to a question about the need for foreign help, that it was necessary3). A couple of versions of this article, changing as the evidence accumulated year by year as the 30 year rule unfolds in the Kew Gardens archives, were published in the Zimbabwe Independent. A longer version of the 2004 article appeared in the Review of African Political Economy.4

‘Todays’ “imperialists” were those who nurtured Mugabe’

Sunday Independent (Johannesburg, South Africa) January 20, 2008Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe claims to have been locked in conflict with all things British for a long time. Celebrating the EU’s decision to welcome him to the Lisbon summit with African heads of state late last year, he gloated at the “disintegration” of Britain’s “sinister campaign … to isolate us”. At the September 2007 UN General Assembly meeting, he declared Zimbabwe “won its independence … after a protracted war against British colonial imperialism which denied us human rights and democracy”. Mugabe said that British colonialism was – and is – “the most visible form of [Western] control” over southern Africa, the negation of “our sovereignties”. He decried Messrs Bush, Blair and Brown’s “sense of human rights [which] precludes our people’s right to their God-given resources”.

Yet investigation of Mr Mugabe’s history with the British ‘colonialists’ shows he was eager to co-operate with them. He embraced their notions of human rights and justice. Archival evidence shows he was close to these ‘sinister’ forces, in 1970 writing personal letters and telegrams from Salisbury’s gaol to Prime Minister Harold Wilson to support his wife’s stay in England. The British also helped him eliminate a group of radical young guerrilla soldiers threatening his precarious hold on the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) later in that decade.

In 1967 Mugabe’s wife Sarah, often called Sally, received a scholarship to study secretarial science in London whilst her husband was imprisoned. The Ariel Foundation was her sponsor. Founded by Kenneth Kaunda’s one-time advisor Dennis Grennan and funded largely by the tobacco enriched Ditchley Foundation, Ariel was devoted to introducing African nationalists to western politicians and capitalists. Mrs. Mugabe needed special authorisation from the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office for her studies. The FCO telegram to Accra (where she, a Ghanaian, was residing whilst her husband was in jail) authorising her entry permit says Ariel “is well-known to us”. In scribbles, it asks: “would you wish to have this on your files? If not, it can be destroyed.”

Mrs. Mugabe studied for the next two years, while also working as the director’s personal assistant and a dress-making teacher at the Africa Centre, in Covent Garden [IMAGE 3]. However, by the end of 1969 Home Secretary Mervyn Rees wanted her out. Mrs. Mugabe’s marriage to Robert did not allow her citizenship in the illegally independent state; thus the British owed her none of the protection due to the pariah’s residents. The Home Secretary told her to return home to Ghana. Grennan, in whose home Mrs. Mugabe resided – ‘”she was like a sister to my children”, he said in an August 2007 interview – mounted a petition campaign for her to stay. Colin Legum’s Observer articles helped too: to examples of white Rhodesians in England with dubious legality, Legum suggested things might have been different if Mrs. Mugabe had shared Mr. Smith’s race. The petition garnered nearly 400 parliamentarians’ signatures. Victory ensued. Legalities notwithstanding Mrs Mugabe could stay.

Perhaps Robert Mugabe’s telegram and letter to the then Prime Minister, Harold Wilson helped too. His and Sally’s entreaties to various ‘imperialists’ indicated their willingness to utilise empire’s services. Hoping humanitarian suasion would dissolve legalities, they employed the moral imperative of human rights discourse.

On 23 February 1970 Mrs. Mugabe wrote to Royal African Society director Maurice Foley, who had been importuned by Ariel Foundation’s executive secretary Anthony Hughes to take up her case. Sally Mugabe wanted Foley’s advice on how to “touch the hearts of the decision makers”. Hughes had opined to Foley that Mrs. Mugabe’s case was “exceptional” due to “human and political factors”: her trials and tribulations had brought her to a “breakdown”. In any case the British state should take on responsibility for the residents of a rogue state. “Surely”, he wrote, “Britain has a moral duty to alleviate, not worsen, her unhappiness”. In a letter to MP Bernard Braine, Hughes refers to “Robert” as if they were mutual friends. He reminds Braine that “for … personal reasons” the Ariel Foundation thought it “appropriate to bring Mrs. Mugabe to Britain in order to help her obtain further skills …”

Robert Mugabe’s June 8 1970 telegram, addressed directly to Harold Wilson at 10 Downing Street “appeal[s that] you recognise her status and grant residence permit till my release from political detention”. A three page letter follows a day later, documenting the case’s history. Mugabe pleas on legal grounds, but ends with “more than that”: i.e. the British state’s “moral responsibilities towards […] persons in my circumstances [and] their wives […]”.He closes with a request, “Sir, that you personally exercise your mind on the case … so that justice is done to my wife and myself”. The postscript follows: “I regret that the consequences of my writing this letter will inevitably be a surcharge on you, Sir …”

Mugabe’s and his interlocutors’ language is laden with the human rights discourse so derided in his speeches of today and used with such slipperiness by the ‘west’. Mugabe’s words are Victorian and moralistic, pleading yet almost secure in assuming idealistic yet rational and middle class action. His appeal to justice goes beyond the letter of the law and the strictures of sovereignty. It’s no wonder that his London friends lauded his cool intellect and asceticism (in contrast to Joshua Nkomo spending all their money on women and drink, Grennan said).

Six years later, in the aftermath of national chairman Herbert Chitepo’s assassination and ZANU’s leadership vacuum, Robert Mugabe’s climb to the top of the party’s hierarchy seemed threatened by a group of young and radical guerrilla soldiers. The Zimbabwean People’s Army (ZIPA) had taken the liberation struggle back from the hands of those who had engineered a ‘détente’ process intended to create a pliant state to replace Ian Smith’s, and had come close to uniting Zimbabwe’s rival nationalist parties to boot. Archival evidence suggests the British helped Mugabe win this battle against Zimbabwe’s youthful soldiers. ZIPA was resisting going to Henry Kissinger’s Geneva conference behind one leader alone. They supported a united front.

As arrangements were being made for the conference, on September 29 1976 Minister of State for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Ted Rowlands telegrammed home from his Gaborone meeting with Joshua Nkomo, leader of Zimbabwe’s ‘other’ liberation movement, that “Mugabe was … controlled by the young men … in Mozambique.” The British were worried that they were a bit too radical for a conference designed to usher in a Zimbabwe compatible with their hopes for their last colony. It would be essential to convince the “young men” controlling Mugabe – who could, as the British ambassador in Maputo put it “turn out to be African Palestinians” to lay down their arms and go to the conference. One way to do this would be to offer their host – Samora Machel of Mozamibique – some assistance if he co-operated. Sure enough, an interest-free loan of £15 million (in two parts) was arranged and Machel told ZIPA’s leaders to go to Geneva. On their return, he agreed with Mugabe’s request to jail them. Mugabe was no longer under their control, and went on to consolidate his leadership of ZANU. The rest, as they say, is history – a history for which Mugabe has much to thank the British, who managed to create their own form of ‘blowback’.

Unlike a real journalist, it was impossible for me to marshal the intellectual energy to write during the election period. What I could notice when I had time to talk to Zimbabweans not caught up in political parties, the charade of election observation missions and the politically parallel processes of ‘civil society’ organizations was the intense faith – indeed certainty – held by 95% of the people I spoke to that Mugabe would go this time. There were scores of examples of the will to see ‘change’. A woman police officer told me that “God will help us to democracy; he does not work for only one man”. On the voting day a soldier on leave in Mbare refused a call-up to the Casspir base because he “hadn’t voted yet”. It was a good thing the colonel on the other end of the cell-phone couldn’t see his red finger; and I wondered, had he voted once in the barracks and once in his household’s ward? A peasant Headlands trekking to Security Secretary Didymus Mutasa’s rally, wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the image of the man who once said Zimbabwe only needs six million people told us, when asked if he would vote for Mutasa, “what’s on my T-shirt is not in my heart: my vote is my secret!”

Within a day of the March 29 election Stephen Chan’s young and older friends emanating from his association with the country since 1980 text-messaged and telephoned him what are probably the most accurate results: a 56% victory for the MDC in the parliamentary race.5 The following article was conceived in the glory of that moment, when a few days after Chan’s poll the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission announced the official results of the parliamentary elections. The third article arrived at the Toronto Globe and Mail about a week after the Movement for Democratic Change announced – inaccurately – its 50.3% victory. The day after that announcement, the Zimbabwe Election Support Network estimated a tally of around 48-43 in favour of Tsvangirai. Away back in third place was the reluctant of-but-not-quite-in ZANU-PF Simba Makoni. He was often named ‘Chicken’ or ‘Henry Albert’ by his colleagues to highlight his extreme reticence to help the South Africans challenge the ruling party from any source except the working class rooted MDC, and to contrast with his lionic nomenclature. Whilst his former colleagues in ZANU-PF are establishing military rule by terror Makoni’s silence makes him seem complicit.

Make Mugabe an offer he can’t refuse: The country’s civil society groups need help from South Africa if civil war is to be averted

Globe and Mail (Toronto, Canada) April 9 2008The text message was brief, yet it summed up years of struggle: “WE HV WON.” It was sent to me last Wednesday by Tamuka Chirimambowa, the battered and exiled University of Zimbabwe student leader, probably the youngest man to contest a Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) primary. The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission had recognized the parliamentary victory of his MDC-Tsvangirai party - something the commission’s predecessors should have done eight years ago.

Nothing, in my 30 years of fascination with Zimbabwean politics, has moved me more than that moment.

With the 99 seats - fewer than what we believe to be the real total, but not bad for a corrupt commission - it seemed as if a decade of hard work had finally paid off. Robert Mugabe’s party, ZANU-PF, was awarded an inflated 97 seats in the legislature, but the commission clearly felt it could not manufacture more than that without negative reactions in the streets and around the world. Even the seasoned vote-riggers and crafty counters could no longer stem the tide of a people’s victory over an economically disastrous and twisted form of crony capitalism.

What the commission was able to do was manipulate the vote tally close enough to the wire to make it look as if ZANU-PF would come close to a majority of votes cast, rather than a minority of single-member constituency seats, to prepare the way for a presidential runoff in 21 days.

In all likelihood, the opposition really won these votes, as it has in elections since 2000, but with ZANU-PF, elections are run on alternative grounds.

Now everything hinges on the presidential runoff and the trade-offs preceding it.

Zimbabweans still had reason to be happy: A decade of stolen elections appeared to be overturned and the corrupted counters had to admit it. By the weekend, however, pessimism returned as ZANU-PF threatened to postpone the runoff for up to 90 days and announced a recounting of the presidential poll.

The MDC’s efforts to get the courts to declare a real count were refused. Displays of authoritarian force - arresting foreign journalists, raiding the MDC’s media headquarters, invading more white-owned commercial farms - by the president’s special troops and the easily hired “war vets” did not bode well.

In 2005, even though Mr. Mugabe won the parliamentary elections, the government carried out Operation Murambatsvina, (meaning Drive Out the Trash), a clearing of urban slums where many people had voted for the opposition. More than two million people were uprooted and the livelihoods of more than 700,000 destroyed. No one wants to see this repeated, especially since this time, the violence would spread beyond the cities to the country, because even there Mr. Mugabe has been rejected.

The ZANU-PF core is not only rotten: It is split. If the BBC can web-cast images of last Friday’s politburo meeting, it’s clear that those pretending loyalty to the president are fickle. They are selling views of the Last Supper for a pittance. With the top layers of its military and security forces split down the middle, and a majority of the junior ranks opposing a crackdown on the opposition, Zimbabwe could easily fall into civil war.

Historically, when ZANU-PF has been confronted with a leadership vacuum, it has taken months of bloodshed, combined with regional and international action, to find a new leader. Anyone familiar with the party’s mid-seventies crisis will know there is little hope of peaceful accommodation now. Then, national chairman Herbert Chitepo was assassinated, a group of militant young leftist unifiers and their supporters were eliminated and a threatening subtribal clique was later tucked away in pits and Mozambique’s prison camps. That paved the way for Robert Mugabe’s pedestal of power. Once in control, he wiped out the remnants of Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe African Peoples Union, a group allied with Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress.

Only one thing stands in the way of this happening again: Zimbabwe’s vigorous civil society movements. From the workers’ unions in the MDC to the intellectuals in the National Constitutional Assembly and the vast array of human-rights organizations, these people deserve credit for the push for democratization. In their own way, they match the youthful zeal and analytical acumen of the young guerrillas who led ZANU-PF in the mid-1970s. And they are not as vulnerable as their predecessors, because they can escape Mr. Mugabe’s reach in global civil society and they man crucial spaces in the Zimbabwean political economy.

But what they need now is for the regional power, South Africa, to wield its influence and help them finish the job. It did so in the 1970s, when the apartheid regime of John Vorster pushed out Rhodesia’s Ian Smith, and more recently, when the ANC provided succour to Mr. Mugabe and stymied the MDC.

Yet South Africa appears to be backing off from the straw that could break the straining ZANU-PF’s back. Does it worry about African politicians’ worship of sovereignty, that fig leaf for naked emperors who have been in power too long? Does it not see the way of new leaders such as Tanzanian and AU President Jakaya Kikwete, who worked so effectively in Kenya a few weeks ago?

Why cajole the worst of the Mugabe mafioso? Why not simply use one finger - or one breath - to topple this wavering regime? All it would take would be an offer that could not be refused.

Mr. Mugabe, Reserve Bank chairman Gideon Gono, recalcitrant military leaders and backers such as arms-dealer John Bredenkamp could be given one-way tickets to the Bahamas, where some spent Christmas holidays.6 This was done with Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a much nicer man who moved from Haiti to Pretoria, and it could be completed with much less bloodshed.

The possibilities are boundless at this moment - but if it passes, if this possibility for progressive and democratic governance does not happen, many will view the South African state as driven more by sympathy with dictators who abuse the discourse of pan-Africanism than by the true democrats who seek to lead the people.

As the above words indicate, the joy was short-lived. ZEC took nearly a month to massage the presidential poll to its 47.9% for the MDC, 43.2% for Mugabe, necessitating a runoff to reach a 50%+1 winner. This was subsequently set for June 27: already, at the time of writing (May 21, 2008), thousands have been run out of their homes, tortured, and nearly forty MDC supporters killed. In the meantime the Zimbabwe Liberator’s Forum, a group of war veterans whose aims are diametrically apposed to those who have appropriated that label in the service of ZANU-PF, whose leadership is composed of the young men who so spooked Mugabe in 1977 (as discussed parenthetically above in ‘Todays’ “imperialists” were those who nurtured Mugabe’7) held a press conference advising the parliamentarians to take control. The made the front page of the Cape Times thanks to journalist Peta Thornycroft’s efforts.

David Sanders, a Zimbabwean medical doctor who in the seventies joined ZANU-PF’s refugee camps in Mozambique and now works in Cape Town directing the University of the Western Cape’s public health programme, wrote asking me to help him write an article remembering Mugabe’s history vis a vis the ‘left’ in Zimbabwe and as an entrenched authoritarian. I was half way there in my attempts to persuade the Mail and Guardian, South Africa’s intellectuals’ spreadsheet, to publish something to this effect. One hour late for editor Ferial Haffajee’s deadline, it went to the Cape Times. I also sent it to the Toronto Globe and Mail, where it ended up on the online edition. This resulted in an online discussion later that week, in which I had to respond to questions and comments such as ‘Mugabe was always a commie/thug’, ‘don’t many Africans wish they were still under colonial rule?’ and ‘how long will it take South Africa to reach Zimbabwe’s condition?’ Many of these questions made me wonder about the fate of the Canadian educational system in my absence.

History lessons for Zimbabwe’s opposition: Talk of vote rigging, international intervention and governments-in-exile merely buys time for the dictatorship

DAVID MOORE AND DAVID SANDERS

Special to Globe and Mail Update April 17, 2008 at 7:18 PM EDTOnly Robert Mugabe and his cronies benefit if Zimbabwe’s deepening, desperate impasse remains. The concatenation of vote rigging, international intervention and talk of governments-in-exile merely buys time for the dictatorship.

As the regime’s sell-by date lingers, Zimbabwe rots. Its whirling decline and rocketing repression bring more brutality, nastiness and pestilence to all but the parasitic elite. Any government of “national unity” – the South African and international community’s mutual mirage – will fail unless it encompasses the popular will demonstrated by the Movement for Democratic Change’s fourth victory since real electoral races began in 2000.

A unity government will only consolidate Zimbabwe’s exchange-rate-rich bourgeoisie. Progressive elements of the MDC and civil society can either accept this blight or halt Mugabeism by other means. Some historical lessons might enable the means and ends to a better prospect.

Zimbabwe’s political past tells us that Mr. Mugabe has answered challenges with repression for 32 years now. Back then, he was opposed by constellations resembling today’s democratic impulses and radical projects. There were elements of civil society, younger generations, party-building efforts, radical democracy, pushes to national unity – even factions of the military. If the democrats against him now forget this history, they’re myopic. If they remember its ideological and political elements but ignore the military, they are utopian. Coercion, consent and negotiation were wrapped up in the war of liberation. The Zimbabwean state’s current heavy securitization means the military role still cannot be ignored.

In 1975, efforts by South Africa and Zambia to create a government-in-waiting of national unity among factions of Zimbabwe’s national liberation movement (for which Mr. Mugabe was released from Rhodesia’s prisons) failed. Zimbabwean African National Union national chairman Herbert Chitepo was assassinated and the party disintegrated.

A group of young Marxists filled the vacuum, restarting the liberation war. Resembling some of today’s civil-society activists, they tried to unify liberation armies, establish innovative educational structures and work with progressive regional power-brokers. However, in 1976, Mr. Mugabe travelled to Mozambique to join the eastern flank of the liberation struggle. His move to the top culminated in his alliance with British and U.S. foreign-policy makers who sought to stem the rise of Zimbabwean radicalism. By early 1977, those attempting to unify the armies of ZANU and ZAPU – the Zimbabwean African People’s Union, led by Joshua Nkomo – were dumped in Mozambique’s prisons at Mr. Mugabe’s instigation. Hundreds of young supporters were brutally incarcerated in ZANU training camps.

Although these militarily and ideologically savvy young Turks trained thousands of recruits in the Tanzanian and Mozambican camps, they failed to make strong alliances with the core of their army’s security forces. Mr. Mugabe brought the leaders of the military’s old guard to his side after their release from Zambia’s prisons, where they were held under suspicion of having murdered Mr. Chitepo. This was the undoing of the new united army, ZIPA. In 1978, more “dissident” cadres were tortured and imprisoned in Mozambique. After independence, an assault on ZAPU in Matabeleland by ZANU’s notorious 5th Brigade logically followed. As many as 20,000 were killed between 1982 and 1986.

In 2000, ZIPA’s core reappeared in the Zimbabwe Liberators’ Platform, genuine war veterans countering the many posers enrolled in ZANU-PF’s land-invasion strategy against the MDC. The veterans’ initial activist inclinations were resurrected as they joined the Crisis in Zimbabwe Coalition, which was temporarily paralyzed by secret police infiltrators.

Now back in action, it urged last week that parliament be immediately sworn in to oversee the electoral process’s next stage. It called for genuine liberation war fighters and security commanders to “uphold their constitutional duty to respect the outcome of the election as the genuine sovereign expression of the popular will of Zimbabweans. To act otherwise would be a treasonable offence for which they will stand accountable and answerable jointly and severally.”

This statement echoes ZIPA’s recognition of the importance of the fusion of military, civil and political fronts. Now, civil society and party activists must look to the soldiers and police, most of whom are from the working and middle classes. They suffer along with their families, and most do not support Mr. Mugabe – the forces meting out the current repression are paramilitary and ragged “war vets,” not regular troops.

It may be that peace-loving people, including intellectuals, will find it necessary to resist by force the violence of the Mugabe thugs. In any event, the task at hand is to persuade the fusion of progressive fronts to take forward the process begun in 1975.

Progressive Zimbabweans must make strategic alliances and maintain the mobilization. The next stage is just over the horizon.

David Moore teaches politics and development studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and has been researching and writing on Zimbabwean politics since 1984. David Sanders, a Zimbabwean, heads the School of Public Health University of the Western Cape.

Finally, as the ‘results’ of the presidential poll were about to be announced – when, as someone rather close to the process told me, the ZEC counters told the generals “we just can’t rig any more” – the acting news editor of Durban’s Sunday Tribune asked me to write 900 words on ‘what might happen if (or was it ‘when’?) the MDC wins?’ The following words spilled out whilst waiting for a plane that was three hours later than expected because South Africa’s flagship airline had forgotten to process my online ticket. They may be too optimistic about the party that has been in waiting for nearly a decade, and they are in retrospect, too pessimistic about the role of the trade unionist left in the party, which actually has an impressive calculation by which the MDC will be measured if it ever gains the state: let us hope, though, that they blend to merge the extremes of hope and scepticism (and that they don’t justify the maltreatment of the Welshman Ncube faction just because it consists of ‘right-wingers). The next weeks and months will forge a new Zimbabwe; let us anticipate it won’t tumble to depths from which it will be impossible to reach a new surface.

‘Zimbabwe offers a lesson on the perils of hero worship’

Sunday Tribune, (Durban, South Africa), May 4 2008

If Robert Mugabe’s legacy has performed any service to humanity it’s this lesson: never hero-worship a politician or party. How many people – especially in and around Zimbabwe – are wondering ‘why did we ever support Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union?’, much as with many fellow-travellers through history: why Stalin, why Mao, why Pol Pot? How could we have ever aided and abetted these tyrants? In Africa, the broad churches of liberation movements ask the same questions as their heroes fade into normalcy. So too for those with high hopes of liberal democratisation: what happened to Zambia’s (Fredrick) Chiluba? Kenya’s (Mwai) Kibaki? Ethiopia’s (Meles) Zenawi? These truths and the questions they raise need application to the prospect of Morgan Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change in power as much as to any political party anywhere.

Then as now, the complex contradictions of Africa’s political economy transmogrified to the political scene will keep observers bemused. Civil society’s struggles to maintain both liberal and socio-economic justice agendas will continue. Social movements will luta continua against looting continua as many freedom-loving political preachers turn into an ostentatious – potentially brutal – predatory elite. This much is certain in Zimbabwe’s new dispensation.

Yet an MDC victory – if not directly with the 50.3% tally it claims, but with a run-off, a Government of National Unity, or both – will mean a real shift in Zimbabwean and regional politics. If the Southern African Development Community, the African Union, and/or the United Nations meet Tsvangirai’s demand to observe a presidential run-off in minute detail across all phases (with armed monitors – the ZANU-PF hawks in the Joint Operations Command know no other language) MDC victory is certain. Already, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission has told the hawks that the ballots can be rigged no further than 47.9% for the MDC to 43.2% for ZANU-PF. The victory of ballots-on-the-polling stations’ walls – Thabo Mbeki’s legacy to regional democracy – has guaranteed that. The next step? Stop the already rampant pre-run-off repression. Could Mbeki cease that fire and save his reputation?

If this victory transpires without dilution through a South African cloned government of national unity, it will be the culmination of nearly a decade of struggle: a long time for a free and fair election. Even a GNU on the real victor’s terms, rather than a watered-down Pretoria model, will be a triumph for a party that has suffered three and a half stolen elections, hundreds of murders and beatings, and treason trials. During this vicious interregnum it has avoided the excesses of internal fracturing scarring Zimbabwe’s political history. Its reconciliatory ethos will be sorely tested against the desire for retribution in the days to come.